SECTION 06

Racial Violence and Terror

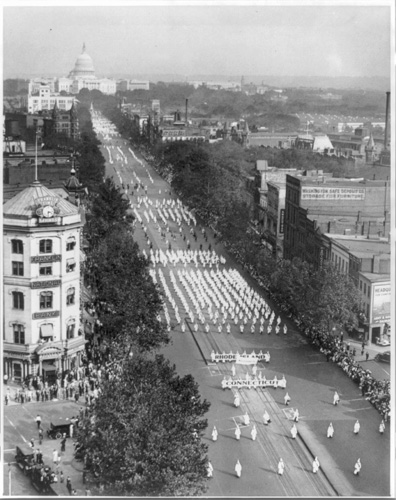

Ku Klux Klan parade (1926).

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Yet, throughout the nation, attempts to organize a black freedom movement were directly confronted by racial violence. Founded in 1866 by former members of the Confederate Army, the white supremacy group the Ku Klux Klan sought to obliterate the gains towards greater equality of all people made during Reconstruction through vigilante violence and intimidation. By the 1880s, after President Grant passed the Civil Rights Act of 1871, the Klan had largely ceased to exist as a distinct organization. However, in 1915, with the release of the popular film, Birth of a Nation , white racists reestablished this vigilante organization, which grew rapidly. The migrations of Black Southerners and Eastern Europeans as a result of World War One had vastly altered urban space and places of work. The Klan, seeking to capitalize on class anxieties about jobs and status, worked vigorously to build coalitions between the powerful Southern elite and white workers. By the early 1920s, the Klan claimed between two and three million members, and controlled hundreds of elected officials and several state legislatures, not only in the South. The underground society hid behind the anonymity of white sheets to mask their identities. Although their attacks were primarily directed at disrupting and terrorizing the lives of African American men and women, the Klan also went after communists, Catholics, Jews, and other groups that threatened their notions of white supremacy and power. Their symbol, the burning cross, was a perpetual reminder of the threat of hate and terror.

Frequently the Klan used false allegations of sexual violence against white women as a justification for their terrorizing of black communities. Despite well-documented acts of terror and murder – frequently lynchings and burnings – Klansmen were rarely prosecuted or convicted for their crimes. However, lynching, racial terror, and vigilante violence were not just enacted by members of the Klan. Between 1880 and 1951, at least 3,437 black and over 1,000 white people were lynched. The violence and racial terror set forth by the Klan was frequently directed at entire communities throughout the nation.

On 31 May 1921 the Tulsa Tribune , a local newspaper, published an article and editorial that incited white mob violence against black Tulsans. An estimated five to ten thousand whites, including several hundred deputized by the police department, participated in three days of violent attacks against the black community. Blacks were assaulted with machine guns, airborne gunfire, and incendiary devices dropped from the air. Glenwood, the most affluent section of the African American community, was targeted for destruction. Widely known throughout the nation as the “black Wall Street,” Glenwood was famous for its economic and cultural achievements. An estimated six thousand black Tulsans were arrested, and 9,000 became homeless as over 1,200 homes were destroyed. An unknown number, perhaps as many as 300 African Americans, were killed. Many of the victims were buried in mass graves and other corpses were thrown into the Arkansas River.

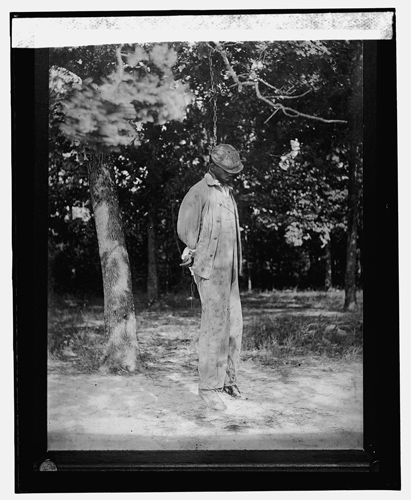

Lynching victim, 1925.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Less than two years later, following on the heels of lynching throughout the state of Florida, the residents of the African American town of Rosewood, Florida were brutally massacred following false claims of rape. The affluent black community was completely obliterated following mob violence. Although two white train conductors were able to evacuate some Rosewood residents, the majority were killed.

These attacks, like those that occurred in Red Summer 1919, did not just take place in the Deep South. Throughout the Midwest and the Northeast, similar, if smaller, occurrences of mob violence terrorized vibrant black communities. In Rhode Island, Klan members burned a black school to the ground. In Indiana, the Klan was a relatively public organization and had the highest rate of per capita membership in the country.

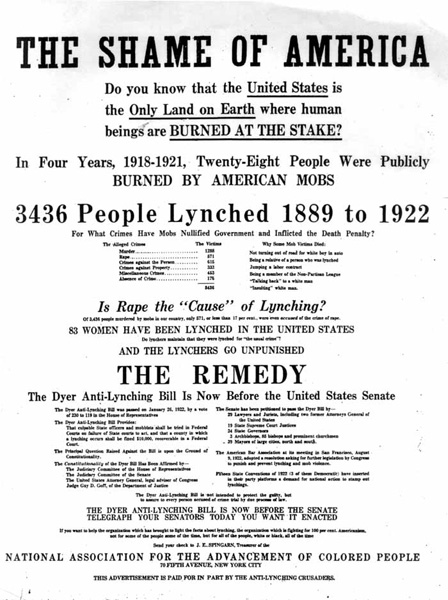

"The Shame of America" NAACP ad in support of Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, November 1922.

Source: New York Times, November 23, 1922. Reprinted at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6786. Last accessed December 5, 2008.

As a response to this violence and human atrocity, Leonidas Dyer, a Republican senator from Missouri, introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress in 1918, and it passed through the House of Representatives in 1922. The Bill, which promised "To assure to persons within the jurisdiction of every State the equal protection of the laws, and to punish the crime of lynching,” was never passed by the Senate. Southern senators from Jim Crow states that had disenfranchised black voters were adamant about protecting those who preserved white political and economic control through terror. A similar bill was proposed in 1935, calling lynching a federal crime, but Roosevelt refused to support it, claiming that white voters would never forgive him. No bill made it through Congress.

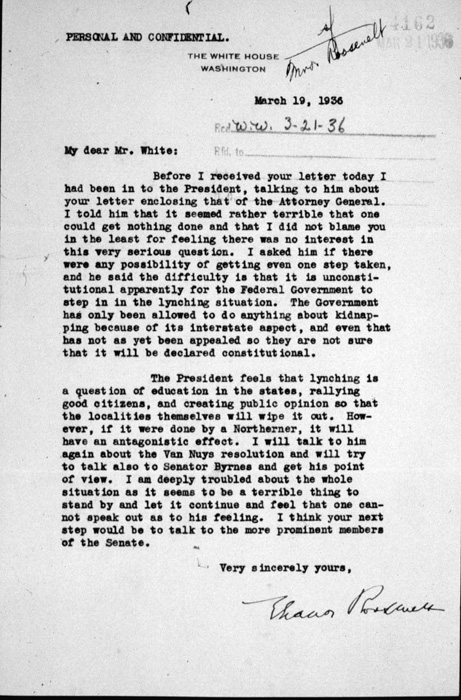

Eleanor Roosevelt's letter to NAACP's Walter White on lobbying against lynchings, March 19, 1936.

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC.

Despite the attempts to destabilize the organization, the Klan found new strength in the post-World War Two landscape. Even as racial segregation was challenged by new urban politics and on factory shop floors by the migrations, the Klan re-emerged in force. As the black population in Los Angeles County, California, reached 200,000 by 1946, the Ku Klux Klan began to appear on the West Coast. Klan organizations were formed throughout the South, and were reported active in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In New York, the state attorney general estimated that there were 1,000 Klansmen in his state alone in the late 1940s. Nevertheless, both the Klan and the frequency with which racial violence was enacted began to lessen as the 1940’s drew to a close. With the movement in the national political climate towards civil rights, and the need to promote democracy as a model to the world in the midst of the Cold War, outright violence was less and less acceptable to the political leaders of the nation.

Related Resources

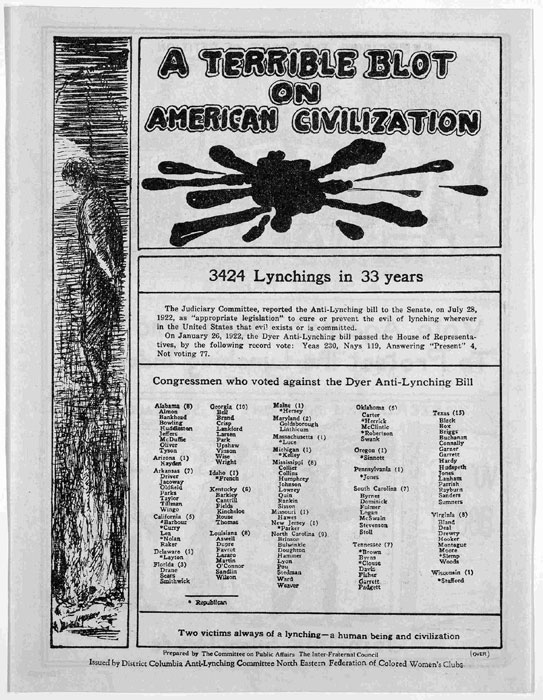

Flyer advocating the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, ca. 1922 (Slide 1).

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure.

Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

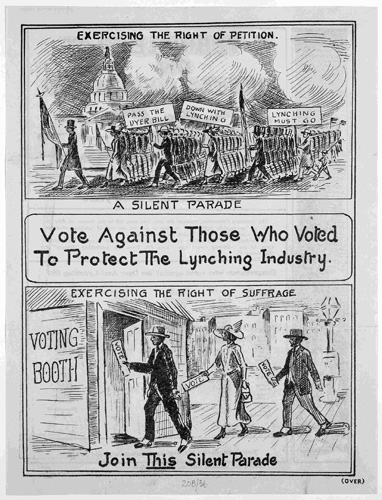

Flyer advocating the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, ca. 1922 (Slide 2).

In 1918, Congressman Senator Leonidas Dyer introduced the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill to Congress, which passed the House of Representatives in 1922, but failed to win passage from the Senate. This flyer, published by the DC Anti-Lynching Committee of the Northeastern Federation of Colored Women's Clubs, called for the passage of the bill and identified those representatives who did not vote for the measure.

Source: Rare Books and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress, Washington, DC.

"The Shame of America" NAACP ad in support of Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill, November 1922.

In November 1922, the NAACP ran this ad in the New York Times and other newspapers advocating for the passage of the Dyer Anti-Lynching Bill.

Source: New York Times, November 23, 1922. Reprinted at http://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/6786. Last accessed December 5, 2008.

Eleanor Roosevelt's letter to NAACP's Walter White on lobbying against lynchings, March 19, 1936.

In this letter to the NAACP's Walter White, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt detailed some of her efforts to lobby the President on behalf of the anti-lynching cause.

Source: Library of Congress Manuscript Division, Washington, DC.

Lynching victim, 1925.

Between 1800 and 1951, at least 3,437 black people were lynched in acts of vigilante terror that targeted black men often falsely accused of sexual violence against white women.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Ku Klux Klan parade (1926).

Ku Klux Klan parade Washington, D.C., on Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, September 13, 1926.

While the original Ku Klux Klan declined in the 1880s, white racists reestablished the vigilante organization in 1915, seeking to capitalize on class anxieties about jobs and status. By the early 1920s, the Klan claimed between two and three million members, and controlled hundreds of elected officials and several state legislatures, not only in the South. The group's parade down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC highlighted the Klan's strength and boldness.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.