SECTION 12

McCarthyism

By the end of 1946, the Soviet Union and the United States had reached a clear breaking point in their relations. From the Soviets’ perspective, the Americans were ungrateful for their preeminent role in the anti-fascist war effort, and lacked any critical understanding of their domestic and foreign requirements needed to restore peace and economic order. The Soviets had lost 20 million men and women in World War II. The Soviet Union was simply in no condition to fight another war, but it did feel that its national interests had to be preserved. The Americans were driven by other motives. American corporate interests were concerned about expanding investments abroad and reducing or eliminating all pro-labor legislation sponsored by the New Deal at home. The anti-communist campaign permitted them to do both, as well as to flush suspected leftists out of positions of trade union authority.

In March 1947, Truman asked Congress to spend $400 million in economic aid and military hardware to halt leftist movements in Turkey and Greece. In the following years, five million investigations of public employees suspected of communist sympathies were held. Trade unions were pressured to purge all communists and anti-racist activists with leftist credentials. For many black Americans, communism was refracted through the prism of race, and was viewed in the light of their own particular class interests. For many black industrial and rural agricultural workers, the communists were the most dedicated proponents of racial equality and desegregation. In the 1930s, they had organized a vigorous defense of the Scottsboro Nine, a group of young black men unjustly convicted of rape in Alabama. The Party had sponsored the formation of Unemployed Councils, broad based coalitions of shop floor workers, unions organizers and unemployed workers that, through various organizing techniques attempted to put pressure on employers for workers’ rights, and provided the major force to desegregate American labor unions. Having declared Alabama a “black nation,” the Communist International had placed issues of racial segregation at the forefront of liberating people from inequality, and thus provided new tools for black leaders in their formulation of a freedom movement.

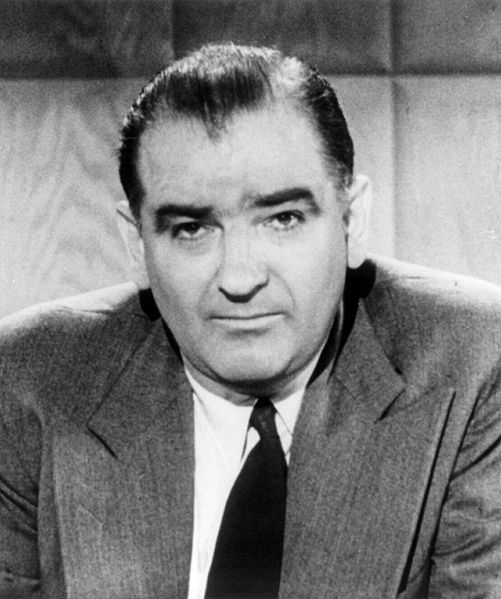

Joseph Raymond McCarthy, 1954.

Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC. [LC-USZ62-71719].

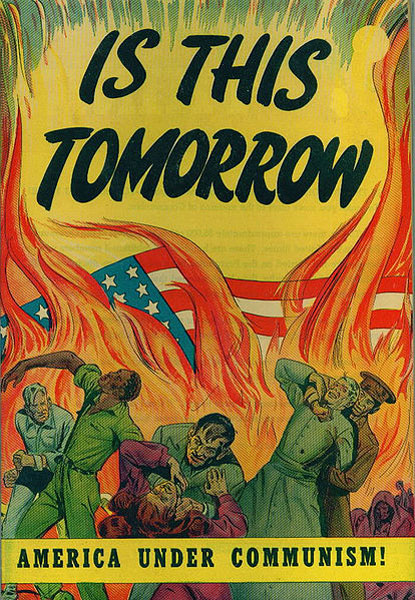

However, the hysteria over communism opened the door for a junior senator from Wisconsin to use the threat of national security breaches in the form of communism to subvert radical politics of any sort. Thousands of Americans were brought up on suspicions of communist affiliations and asked to testify, an experience that caused many people to lose jobs, security, and to live in constant fear. Radicals, even without ties to communism, were subjected to the communist witch hunt conducted by the House of Un-American Activities and Joseph McCarthy.

The most prominent black supporters of progressive and leftist politics at this time were W.E.B. Du Bois and the famous cultural artist-activist Paul Robeson. Du Bois had been an independent socialist since 1904, but had experienced a series of volatile confrontations with revolutionary Marxists. Yet after extensive travels in the Soviet Union in 1926, 1936 and 1949, Du Bois’s view on matters shifted considerably. He concluded that the Soviets’ anti-imperialist positions promoting the necessity for African political independence from European colonial rule were genuinely progressive; he was impressed with the Soviet Union’s extensive domestic educational, social and technological gains. By the late 1940s, he believed that the black liberation movement in America had to incorporate a socialist perspective, and that blacks had to be in the forefront in promoting peaceful co-existence with the Soviet bloc. Robeson, in contrast, was politically closer to the communist movement for a greater period of time. In the late 1930s, he supported the progressive government of Spain against the Nazi-backed Spanish fascists in that country’s bloody civil war. He recognized earlier than Du Bois that the rise in domestic anti-communism would become a force to stifle progressive change and the civil rights of blacks.

As the Cold War intensified, the repression of black progressives increased. Aided by local and state police, a gang of whites disrupted a concert given by Paul Robeson in Peekskill, New York in 1948. HUAC witnesses declared that Robeson was “the black Stalin among Negroes.”[i] In August 1950, the U.S. government revoked his passport for eight years. Officials prevented Robeson from entering Canada in 1952, although no passport was necessary to visit that country. Du Bois ran for the U.S. Senate in New York in the autumn of 1950 on the progressive American Labor Party ticket, and denounced the anti-communist policies of both major parties. Despite wide public censure, he received 206,000 votes and polled 15 percent of Harlem’s ballots. The Truman Administration finally moved to eliminate Du Bois’s still considerable prestige within the black community. On 8 February 1951, Du Bois was indicted for allegedly serving as an “agent of a foreign principal” in his anti-war work with the Peace Information Center in New York. The 82-year-old black man was handcuffed, fingerprinted, and portrayed in the national media as a common criminal.

The pre-eminent black feminist of the time, Claudia Jones, was also brought up on charges of being a communist. Trinidadian born, Jones moved to Harlem and began organizing as the leader of the Young Communist League of New York City. Within a few years, Jones had been elected to the National council for the CPUSA and was an editor at the Daily Worker . Her staunch commitment to worker’s rights and Black Nationalism made her an easy target for the McCarthy commission. Jones was imprisoned four separate times by the United States government, and was deported in 1955. The harassment of black leaders and movements, as well as the fear created throughout radical movements, forced the most effective radical organizing underground. The Cold War had provided new ways of holding onto segregation, and retarding the black freedom movement for over a decade.