SECTION 08

Malcolm X

The intellectual movement known as Black Power was in many respects embodied in the charismatic figure of Malcolm X. Born Malcolm Little in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925, to parents who were active members of Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, when Malcolm was a young boy his father was brutally murdered, probably by white racists. After his mother was institutionalized for mental illness, Malcolm and his siblings were placed in foster care. Later he moved to Boston to live with his half-sister. Years later, Malcolm became a petty criminal, known as "Detroit Red." In 1946 he was sentenced to a 10-year prison term for burglary. While incarcerated, Malcolm became attracted to the teachings of Muhammad, and after some initial resistance became a member of the Nation of Islam (NOI). Following the organization's tradition, Malcolm Little discarded his "slave" surname, and was renamed Malcolm X--the "X" standing for the unknown African heritage that had been lost as a result of the slave trade.

Upon his release from prison in 1952, Malcolm X quickly became an important lieutenant of NOI leader Elijah Muhammad, who soon assigned Malcolm a series of responsible positions. In 1954 he became the head of Harlem's Temple #7, a position he would hold for almost 10 years. Traveling extensively throughout the country, Malcolm X recruited thousands of new members annually through his popular public appearances and powerful outreach efforts to the most poor and oppressed sectors of the black community. In 1961, Malcolm X founded the publication Muhammad Speaks, which became one of the most widely read African American newspapers in the United States. Moreover, Malcolm's quick intellect, wit, and outspoken views attracted the attention of the white national media.

The Nation of Islam taught that African Americans should establish their own state, separate from that of the United States, and that black businesses and organizations should provide goods and services to blacks. Appointed as the Nation of Islam's national spokesperson, Malcolm X gained national prominence--in the early 1960s--as the most outspoken critic of the strategy of nonviolence of the civil rights leadership. For several years, he had attempted to establish a black united front, which was to include a broad spectrum of African American leaders and opinions. However, repeatedly rebuffed by Martin Luther King Jr. and most of the other civil rights leaders, and personally criticized by Thurgood Marshall and Bayard Rustin, Malcolm X ridiculed and condemned the cause of integration as it was being pursued in the early 1960s. Malcolm X aggressively pushed the NOI to play a more active role in efforts to challenge police brutality and to fight for the political empowerment of African Americans. Elijah Muhammad and other conservative NOI leaders opposed Malcolm's new political militancy and began to undercut his position in the organization. During 1962 and 1963, the publication Malcolm X founded, Muhammad Speaks, barred any mention of his name. Impatient with NOI' s refusal to participate more aggressively in anti-racist efforts, Malcolm X broke away from the organization in March 1964.

Two months later, he established the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), with the objective of building a broad coalition of black groups to work jointly to empower the most oppressed sectors of the black community. During the months after the OAAU' s inception, Malcolm X restructured many of his older ideas into a clearly uncompromising program, which was both anti-racist and anti-capitalist. Like W. E. B. DuBois before him, Malcolm X and the OAAU planned to submit to the United Nations a list of human rights violations and acts of genocide committed by the United States against blacks. He was highly critical of the black middle class for buying into the government's anti-poverty agenda, which he believed would do little to help the plight of black city residents.

During the second half of 1964, Malcolm X took a second trip to Africa and the Middle East. In many countries he was welcomed with the ceremony due to a head of state. He met with leaders of anti-colonial movements and spoke publicly before African legislatures and the Organization of African Unity. Upon his return to the United States in late 1964, the level of harassment and death threats against him and his family dramatically increased. His former protg, Louis X (later Louis Farrakhan), publicly attacked Malcolm X as being a man "worthy of death." Historians have subsequently learned that Malcolm X was also under close surveillance by the FBI and law enforcement authorities, which tried to undermine the OAAU. In the days before his assassination, Malcolm X confided to his biographer, Alex Haley, that the level of harassment was so extensive that he no longer believed that the Nation of Islam was primarily responsible for it. In the early morning hours of February 14, 1965, Malcolm's home in Elmhurst, Queens in New York City was firebombed. His pregnant wife, Betty Shabazz, and their four small children were unharmed.

In the last year of his life, Malcolm X successfully completed a spiritual journey from the separatist creed of the Nation of Islam, to the internationalism of orthodox Islam. Unfortunately, he did not have sufficient time to complete his political journey. He remained committed to black nationalism, which he defined as the effort to build strong black-controlled institutions for empowering the African American community. But in the last months of his life, he also spoke about the need for African Americans to challenge the capitalist system. He denounced U.S. involvement in Vietnam and urged African Americans to build solidarity movements with Third World countries.

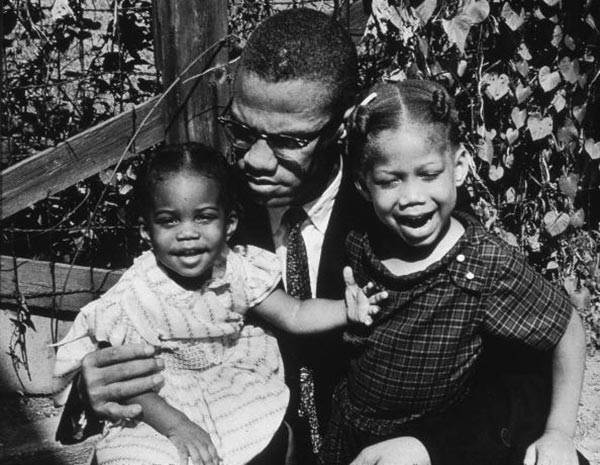

Malcolm X with Family, 1963.

Source: Photo by Robert L. Haggins/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

On the afternoon of February 21, 1965, just before he was due to deliver a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in Harlem, Malcolm X was assassinated by three gunmen, in front of his wife and three of his four children. The perpetrators were later identified as members of the Nation of Islam. The crowd that had gathered for the address overwhelmed one of the assailants before the police took him into custody. Malcolm, who had suffered more than twenty bullet wounds, was transported on a stretcher to the hospital across the street, where he was pronounced dead. In apparent retaliation, the Nation of Islam's Mosque #7 in Harlem was firebombed hours later.

At Malcolm X's funeral, African American actor and activist Ossie Davis eulogized him: "Malcolm was our manhood, our living, black manhood! This was his meaning to his people. And in honoring him, we honor the best in ourselves. And we will know him then for what he was and is--a Prince--our own black shining Prince!--who didn't hesitate to die, because he loved us so."

The influence of Malcolm X on the freedom movement and the intellectual shifts from integration to nationalism and back to a redefined integration has continued to be important. Although many Americans condemned Malcolm X as dangerous and anti-white, his political philosophy toward the end of his short public life was broadly humanistic and internationalist. Malcolm X reached the conclusion that Americans could indeed have a "bloodless revolution," if whites could transcend their historic prejudices against people of color, and if the socioeconomic and political institutions of the country could fully address the needs of the nation's diverse population. Malcolm X insisted that he and his supporters were not "anti-white," but they were "anti-exploitation . . . anti-degradation . . . anti-oppression. . . . The political philosophy of black nationalism, Malcolm X declared, "means that the black man should control the politics and the politicians in his own community. . . . We want freedom now, but we're not going to get it saying, 'We Shall Overcome.' We've got to fight until we overcome."

Related Resources

Malcolm X with Family, 1963.

Then a minister for the Nation of Islam, Malcolm X Shabazz plays with two of his daughters, 1962.

Source: Photo by Robert L. Haggins/Time Life Pictures/Getty Images.

Stories from the Collection: Columbia University Oral History Research Office, CD, 1998, track 08.