SECTION 10

Urban Unrest and Socioeconomic Conditions

The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1965 and the 14th Amendment did little to provide economic opportunities for blacks, poor or professional. In fact, the collapse of manufacturing industries and white flight to the suburbs exacerbated the economic disenfranchisement of black city residents.

Sociologist Kenneth Clark, a key contributor to the legal arguments behind the 1954 Brown decision, observed in 1968: The masses of Negroes are now starkly aware that the recent civil rights victories benefited primarily a very small percentage of middle class Negroes while their predicament remained the same or worse. . . .[T]okens of 'racial progress' are not only rejected by the masses of Negroes but seem to have resulted in their increased and more openly expressed hostility toward middle class Negroes." In urban neighborhoods like South Central Los Angeles, one quarter of all dwellings were substandard, without plumbing, heat, or electricity. About 30 percent of adult blacks were jobless. Blacks in Los Angeles were confined to an area four times more congested than the rest of the city. Overcrowding was endemic and, particularly in the inner cities, blacks suffered disproportionately higher rates of hypertension, tuberculosis, diabetes, and other illnesses. Such intolerable conditions convinced many African Americans that the victories of the desegregation movement were largely irrelevant to the masses of urban poor blacks.

As the quality of black urban life--poor housing, rat infestation, crime, high infant mortality rates, disease, poor public education--continued to deteriorate, community tensions began to rise; so did police violence. The disparities between black city residents and those who lived in the affluent middle-class suburbs finally produced a series of urban uprisings that drew their energy from the alienation and anger of the unfulfilled promise of equality under civil rights. While depicted as riots by the media and government, these uprisings very intentionally targeted the economic sources of oppression in their communities--department stores, downtown storefronts, etc. From 1964 to 1972, hundreds of urban rebellions erupted, leaving a total of 250 deaths, 10,000 serious injuries, and over 60,000 arrests.

On August 11, 1965 a white police officer stopped African American motorist Marquette Frye in South Central Los Angeles (the Watts area). The police suspected him of driving while drunk. An altercation broke out when Rayna Frye, the motorist's mother, arrived at the scene. According to eyewitness accounts, a second officer struck onlookers with his baton, which generated an outpouring of anger and resentment against symbols of white authority. Over the next five days, African American residents of the Los Angeles slum attacked white-owned property, which resulted in the deaths of 34 people, injuries to over 1,000, and the arrests of almost 4,000. California Governor Pat Brown ordered the National Guard to patrol the city of Los Angeles, bringing the total of police, guardsmen, and other law enforcement officers to 16,000. Martin Luther King Jr., Bayard Rustin, and other civil rights leaders came to Los Angeles to encourage an end to the violence.

Governor Brown appointed John McCone to chair a state commission to examine the factors that culminated in the urban uprising. The McCone Report cited high rates of unemployment, substandard public education, poor housing, and the use of excessive force by the police, as the underlying causes. In California, conservatives charged that permissive attitudes (considered "liberal") and civil rights advances had contributed to the civil unrest. These disturbances were a factor in the electoral success of conservative Ronald Reagan as California Governor in 1966. The Watts disturbances were a harbinger of the urban unrest that would soon sweep across the United States in the late 1960s.

As a result of the Watts civil unrest, King and other civil rights leaders concluded that the civil rights movement had to make a strategic shift away from its focus on the rural South toward increased efforts to desegregate America's dilapidated Northern cities. The SCLC concentrated its resources in the North in an attempt to provide job opportunities and better housing and education in the black neighborhoods in the North.

The "long, hot summer" of 1967 witnessed the largest number of black urban uprisings in the country's history. In cities throughout the United States young African Americans, frustrated by high rates of unemployment, rampant discrimination, poor housing, inadequate social services, and police brutality, resorted to acts of public protest and retaliatory violence against symbols of white authority. Many younger African Americans felt that the integrationist strategy of nonviolence was meaningless in the face of the routine use of excessive force by white police officers in their own neighborhoods.

In the summer of 1967, major uprisings occurred in several northern New Jersey cities, including Newark, Elizabeth, Jersey City, and New Brunswick. In the wake of the numerous urban uprisings, President Johnson appointed Illinois Governor Otto Kerner to head a national advisory commission on civil disorders. The Kerner Commission later reported that in the first nine months of 1967, the United States had experienced uprisings in 128 cities. The report warned: "Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white--separate and unequal."

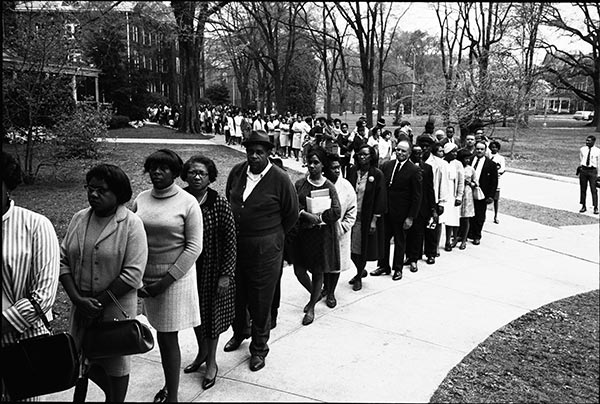

Sanitation workers from Memphis march.

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.

In the aftermath of King's assassination on April 4, 1968, thousands of blacks displayed their anger and grief by destroying white-owned property in black neighborhoods and targeted symbols of white authority, such as the police. In Chicago, 11,000 members of the U.S. Army and the Illinois National Guard were deployed to suppress the civil disorders. In Baltimore, urban violence subsided only after 8,000 federal troops and National Guardsmen implemented a military occupation of predominantly black districts. Rioting in Cleveland's East Side on July 5, 1968 resulted in 22 casualties, 15 of which were police officers, in only one hour.

Traditional civil rights leaders now began to question whether their emphasis on abolishing legal segregation had led them to ignore the social crises of poverty and despair in the inner cities.

Related Resources

Mourners wait to pay respects to Rev. King.

Over 50,000 citizens participated in the funeral procession for the fallen civil rights leader.

Source: Constantine Manos/Magnum Photos.

Burned streets of Washington D.C., 1968.

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., violence erupted across the nation's cities as people reacted to the loss of the civil rights leader. Here, the national guard patrols the burned streets of Washington D.C., 1968.

Source: Leonard Freed/Magnum Photos.

Sanitation workers from Memphis march.

Following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., the sanitation workers he had come to Memphis to support led the National Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial March for Union Justice and to End Racism, April 27, 1968.

Source: Courtesy of Builder Levy, photographer.