SECTION 09

Civil Rights, Voting Rights, and the Selma March

The year 1964 marked a legislative victory for civil rights activists and was a pivotal moment in the political history of African Americans. Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and President Lyndon B. Johnson signed it into law. The Act prohibited the exclusion of blacks from all public facilities and accommodations: restaurants, parks, swimming pools, hotels and theaters. It outlawed the use of federal funds to maintain or support educational institutions that practiced segregation. That same year, the 24th amendment to the U.S. Constitution was passed. By abolishing the poll tax on voting--a restrictive measure used extensively in the South to deny poor black people the right to vote--an increasing number of blacks were able to vote for the first time, thereby exerting an impact on local and national elections.

With the passage of the legislation and the amendment, civil rights activists shifted their attention to enforcing the voting rights of blacks in the South. White authorities, using all kinds of ruses, frequently refused to register black voters. In 1965, SNCC, Martin Luther King and other SCLC leaders came to Selma to organize marchers and generate national media attention around the local campaign for voting rights. The police in Selma arrested King, with 250 marchers on February 1.

On February 4, a federal judge had ordered the Selma registrar's office to process a minimum of a hundred voter applications a day. Almost immediately registrars created new obstacles for black voters. The SCLC decided to once again organize a march for the right to vote. The plan entailed walking along the highway from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, 50 miles away. On March 7, 1965, Hosea Williams led the march. Andrew Young, James Bevel, other SCLC organizers, and SNCC leader John Lewis joined Williams. As marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge along the route, the police, armed with shotguns and automatic weapons, confronted the marchers. The Alabama troopers, determined to stop the marchers, pressed forward in readiness to attack. Governor George Wallace had approved the use of force, if necessary, to halt the march. What ensued was a brutal and sickening attack by police with tear gas, billy clubs and night sticks on the unarmed marchers. More than 600 marchers were assaulted and 17 hospitalized on the first day of the march, known as "Bloody Sunday."

Martin Luther King returned to Selma on Tuesday, March 9, to personally lead 1,500 nonviolent marchers and confront the Alabama State troopers on the other side of the bridge. After kneeling to pray and singing the civil rights anthem, "We Shall Overcome," King ordered the marchers to turn back. He believed that the use of force by the police was imminent and that the symbolic point of walking across the bridge had been made. King's decision disappointed, if not angered, SNCC activists, and even some of the SCLC leadership. Later that evening, white racists attacked several white ministers who had participated in the march. A Unitarian minister, clubbed in the head, died of his injuries two days later.

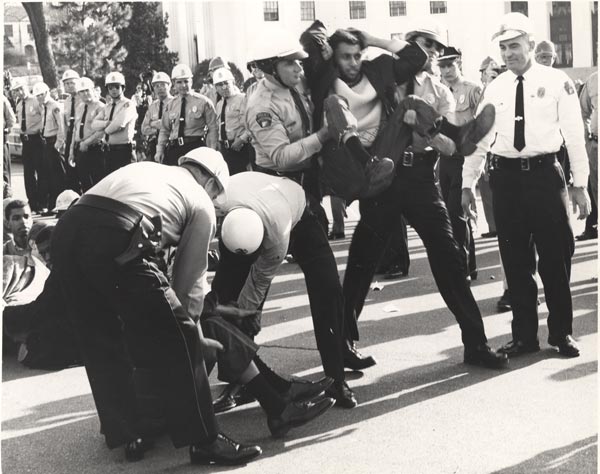

Selma Police arrest peaceful demonstrators.

Source: Alabama Sovereignty Commission, Administrative files, SG13843, folder 8, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery Alabama.

Despite the violence the marchers encountered on two occasions, King and the SCLC courageously planned a third march. After the federal court ruled that Alabama could not prohibit the marches, the march began on March 21. By the time they arrived in Montgomery, the 4,000 who had begun the march in Selma had been joined by more than 25,000 additional marchers. As they reached the state capitol building, which still flew the Confederate battle flag, tens of thousands of marchers celebrated their victory.

The violence in Selma compelled President Johnson to introduce a federal voting-rights bill. In a speech to Congress, Johnson introduced the bill and, using the language of Civil Rights singers, said, "We shall overcome." The Selma-to-Montgomery voting campaign attracted national attention and political support necessary for Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act in 1965 (also known as the Civil Rights Act of 1965).

Millions of blacks--who had been denied the right to vote for nearly a century--had finally won a federal guarantee to exercise their right to vote. In his speech, President Johnson affirmed his support for the goals of the civil rights movement, noting: "We will not delay or we will not hesitate, or we will not turn aside until Americans of every race and color and origin in this country have the same rights as all others to share in the progress of democracy."

The Voting Rights Act almost immediately changed the political landscape of the South. In every Southern state, the percentage of black adults, who were newly registered to vote, rose above 60 percent within four years. By 1969, 12,000 black officials were elected to office, with more than one-third of that number from the South.

Related Resources

Selma Police arrest peaceful demonstrators.

Selma police arresting nonviolent marchers during their first attempt to march from Selma to Montgomery, March 7, 1965. The violence against marchers prompted President Johnson to submit a proposal for a strong Voting Rights Act.

Source: Alabama Sovereignty Commission, Administrative files, SG13843, folder 8, Alabama Department of Archives and History, Montgomery Alabama.