SECTION 07

Mississippi Freedom Summer

The greatest resistance to the dismantling of legal racial segregation occurred in Mississippi. With a huge Ku Klux Klan membership and White Citizen's Council chapters (WCCs) that were tied to lawyers, doctors, judges, and politicians, violence was not just a threat; it was an everyday reality. The WCC, founded in Mississippi, had over 10,000 members who were so successful in their actions that 10 years after Brown v. The Board of Education, schools still remained segregated. The state had the highest lynching rate in the country. Almost 600 people had been lynched between the end of the Reconstruction era and 1968. Indeed, as a result of state's rights, Jim Crow continued to be maintained even as the Supreme Court began breaking down the legal barriers of segregation. After the brutal lynching of Emmett Till in 1955, civil rights leaders focused their attention to the atrocities committed in the name of the law in Mississippi.

The state's segregationist policies had been decisively challenged, however, when James Howard Meredith, a 28-year-old African American, applied for admission to the University of Mississippi in 1961. Officials rejected Meredith's application, and a suit was filed in federal court on his behalf. The U. S. Supreme Court ruled in Meredith's favor, ordering that he be admitted to the University, and U.S. marshals were deployed to escort him to class after the governor of Mississippi personally attempted to block his entry. President Kennedy was forced to station federal troops at the campus as white rioters destroyed automobiles and campus property. By the end of the rioting, two people had been killed and hundreds were injured. Despite personal abuse and racist intimidation, Meredith completed his studies at the University, successfully graduating in 1963.

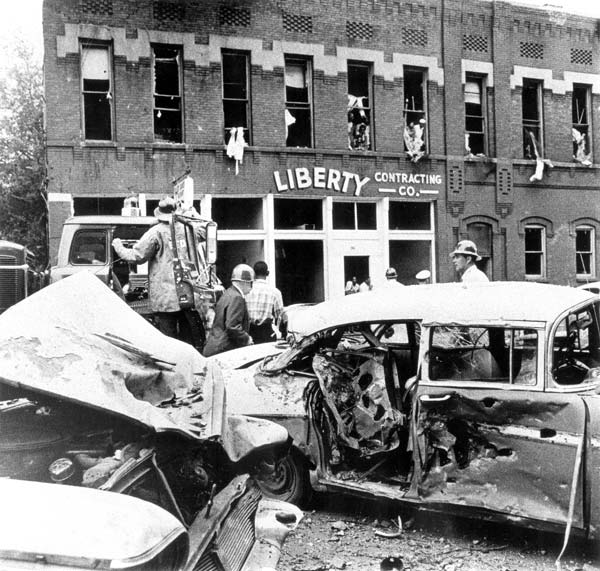

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing.

Source: Courtesy of Birmingham Public Library, Department of Archives and Manuscripts.

Yet, despite the victory at the University of Mississippi, the violence in the state continued unabated. In June of 1963, Mississippi asserted its rightful place as the most racist state with particular vigor. On the night of June 11, NAACP state leader Medgar Evers, who had been instrumental in collecting evidence during the Emmett Till case, was executed in front of his Jackson, Mississippi, home by a white supremacist connected to the Ku Klux Klan. In the nearby state of Alabama, four little girls were murdered when racists bombed the Birmingham SCLC office during a youth day at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

In the midst of the burgeoning violence, community activists decided that the only way to affect change in the most oppressive state in the country would be through the voting system. Activists determined that if they could register people to vote, they could push both legislation and action through the electoral process. In Mississippi however, the fifteenth amendment, banning race-based voting restrictions, meant nothing. Jim Crow laws created literacy restrictions that were imposed only on people of color; people would be turned away at courthouses and schools by police or white citizens council members with guns when they tried to vote.

In 1962 less than 7 percent of the African American electorate in the state of Mississippi was registered to vote - the lowest percentage in the United States at the time. For this reason, SNCC, CORE, and the NAACP targeted that state for intense political action. The organizers were a diverse group of activists. Recognizing that white Americans would be more sympathetic to the cause of civil rights if whites became involved in the effort to build democracy across the South, black leaders recruited white college students to train in the techniques of nonviolent direct action with the objective of registering thousands of new African American voters. The first phase of the project was to develop Freedom Schools throughout the state.

The Freedom Summer project organized 30 "Freedom Schools" throughout Mississippi, which focused on leadership training. Their curricula included reading, mathematics, and African American history. Led by Septima Clark, over 3,000 young blacks attended the schools. These educational institutions, spawned by social protest, became models for alternative grassroots educational programs throughout the United States. The schools were also creating leaders who could participate in Freedom Summer's massive voter registration project. With the help of activists from around the nation, Freedom Summer participants went door to door registering people to vote. After their successes with voter registration, the group launched the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in response to the state's all-white slate for the Democratic National Convention.

Violence against the organizers, however, was relentless. White racist vigilantes and law enforcement officials made a concerted attempt to intimidate and expel the civil rights workers. During the summer of 1964, 30 black homes and more than three dozen African American churches were firebombed or destroyed in Mississippi. On June 4, 1964, three civil rights workers connected with the voter registration project went missing. James Earl Chaney, born in Meridian, Mississippi in 1943, joined CORE at the age of twenty. He became involved in the mobilization of the 1964 Freedom Summer with white activists such as Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, a 24-year-old Cornell University graduate who had just opened the CORE office in Meridian with his wife Rita. On June 21, 1964, Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman were driving from Meridian to Lawndale, Mississippi, when the police stopped them in Philadelphia, Mississippi, for speeding. They were taken to jail but were subsequently released--only to disappear. For six weeks nothing was heard of them.

It was not until August 4 that their decomposed bodies were uncovered beneath an earthen dam. The autopsy revealed that Goodman and Schwerner had been killed by single gunshots to the head. Chaney had been brutally beaten before being shot. The Justice Department subsequently indicted 19 people, including police officers and members of the Ku Klux Klan for their involvement in the murders. Only seven of those indicted were found guilty. The case raised new support for the civil rights cause as a result of the death of two young white men. Individuals who did not know that violence could touch the white community were shocked at the brutality of the killings, and thus widespread support began to pour in for the Mississippi group.

Undeterred and armed with new reasons to address a system that seemed not to be enforcing democracy, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was growing. A new independent political movement, the MFDP, was formed to challenge the state's pro-segregationist Democratic Party. Its membership would grow to 80,000. The MFDP sent its representatives to the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City, demanding the right to represent the people of their state in the proceedings. Unwilling to alienate white southern Democrats, President Lyndon Johnson proposed a compromise agreement according to which the all-white delegation would remain intact and only two MFDP delegates would be credentialed to vote as official delegates. All other MFDP representatives would be classified as observers only.

Fannie Lou Hamer.

Source: Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Most of the mainstream civil rights leadership, including Martin Luther King, Jr. and Roy Wilkins, urged the MFDP to accept the compromise, but they refused. To many progressives in the civil rights movement, the Democratic Party's leadership had betrayed the principles of democracy. In response, Fannie Lou Hamer, a major organizer for MFDP, passionately challenged the exclusionary policies of the Democratic Party, asking "Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we are threatened daily because we want to live as decent human beings?" The MFDP refused the compromise. Their efforts raised major questions about the meaning of democracy and the way in which it could be fulfilled through the political system.

Related Resources

Fannie Lou Hamer.

As the spokeswoman for the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Fannie Lou Hamer traveled to Atlantic City, NJ, with other activists for the Democratic National Convention, August 24, 1964. Although being denied official credentials, the symbolic party became a catalyst for independent black political organizations throughout the country.

Source: Warren K. Leffler, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Civil Rights Leader Medgar Evers Murdered.

Medgar Evers, the NAACP field officer for Mississippi, is assassinated by a shotgun blast. Source: NBC News / iCue.

Fannie Lou Hamer's Testimony at the 1964 Democratic Convention.

At the 1964 Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, a group of African-American delegates from the Mississippi Freeedom Democratic Party challenged Mississippi's all-white delegation to the convention. When Fannie Lou Hamer, a sharecropper, told the credentials committee her story about trying to register to vote in Mississippi, her testimony was broadcast by all three networks, and Hamer became a national spokeswoman for civil rights overnight. Source: NBC News / iCue.

Interview conducted in 1985. Stories from the Collection: Columbia University Oral History Research Office, CD, 1998 track 03.